In its broadest sense, “curriculum” refers to the totality of learning experiences provided to learners. The university offers its students a variety of curricular courses, research guidance, overseas training, and many other opportunities for learning and development. Ultimately it is left up to students to determine how to utilize these opportunities as their own learning experiences, but the university is responsible for designing and furnishing the opportunities.

Below we introduce some key points in curriculum design.

What is Curriculum?

Firstly, let us consider what curriculum is and how to represent it.

1.1 Curriculum and program

- In its broadest sense, curriculum refers to the totality of learning experiences provided to learners, but in administrative terminology “educational program (kyôiku katei)” is used to indicate the most systematized and planned elements of the curriculum.

- In Japan, educational programs up to senior high school level are codified in official courses of study and regulated by approved textbooks. For university education, however, universities and faculties are afforded a considerable discretion to develop their own educational programs.

- In the 1991 amendment (so-called “deregulation”) of the Standards for Establishment of Universities, it was stipulated that “[a] university shall establish the class subjects necessary to achieve its educational purpose of the university, respective faculties, departments, courses, etc., and shall organize the curricula systematically” (Article 19). Quite simply, curriculum is (in the words of Masao Terasaki, one of the leading Japanese scholars in university education) “an expression of the educational intent of the university or faculty.”

- A term related to curriculum is “program.” A program is an organized collection of courses, learning activities, and other elements under a specific educational goal (for example, first-year experience (FYE) program, degree program, study abroad program, etc.).

1.2 Academic curriculum and co-curricular activities

- Opportunities for learning experience provided by the university can be divided broadly into “academic curriculum” and “co-curricular activities.” There are also other activities conducted by students at university, such as clubs, circles, self-organized seminars and self-government activities, which are known as “extra-curricular activities.” The university has an important role to play in supporting these extra-curricular activities, but they are not included in the curriculum.

- An academic curriculum is what is known in the Standards for Establishment of Universities as an “educational program (kyôiku katei).” It is composed of courses in which credit is awarded (required, elective, and optional courses) arranged in a systematic manner. Japan uses a credit system in which undergraduate students are required to earn at least 124 credits (other than six-year programs, such as medicine, dentistry, and pharmaceutical science) in order to graduate, where each course of one credit is comprised of content that requires 45 hours of study time as a standard.

- On the other hand, co-curricular activities are offered or assisted by the university/faculty for educational purposes but for which credit is not usually awarded. One representative example is service learning, where students learn through participation in community service activities in the local area. Other examples of co-curricular activities include university-organized overseas training, internships, and volunteer activities.

1.3 Degree program

- As the name suggests, a degree program is a program leading to the award of an academic degree (Bachelor, Master, Doctor, Professional degree).

- Kyoto University awards degrees of Bachelor, Master, Doctor, Master (Professional), and Juris Doctor (Professional). Details of respective degrees are listed in the Kyoto University Academic Degree Regulations. From the 2012 academic year, the university also offers Programs for Leading Graduate Schools, such as the Collaborative Graduate Program in Design, as interdisciplinary degree programs.

- At Kyoto University, each faculty usually awards one type of degree (two types in the Faculties of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences), but some other universities award different degrees in each department or major, with distinct educational programs offered for each one. For example, Osaka University has 37 degree programs at undergraduate level and 108 at graduate school level, making a total of 145.

- Apart from degrees awarded by a single university, there are also joint degree programs (in which a Japanese university partners with one overseas to organize and implement an educational program and award a degree in the name of both universities), and double degree programs (in which two or more universities in Japan and/or overseas make use of a credit transfer system to enable students to complete their respective educational programs within a certain period and earn multiple degrees). At Kyoto University, for example, a joint degree program is operated by the Graduate School of Letters, and a double degree program by the Graduate School of Energy Science.

1.4 Curriculum map

- Curriculum map is a general term for “a structural diagram that indicates the relationships of correspondence between the courses and the knowledge/abilities students are equipped with [through a degree program], and promotes systematic learning therein” (translated from the glossary to the Central Council for Education report on qualitative transformation of university education, 2012). In other words, the map indicates the relationship among the courses and the sequence of learning in the degree program. The terms “curriculum chart” and “course tree” are sometimes used as alternatives to “curriculum map.”

- Kyoto University has been publishing course trees for all its undergraduate faculties since the 2015 academic year. Moreover, all graduate school curricula have been schematized and published since the 2016 academic year.

Requisites on Curriculum Design

What aspects need to be taken into account when designing curriculum in a Japanese university?

2.1 Diploma/Curriculum/Admission policies

- Since being advocated by the Central Council for Education’s report on The Future of Higher Education in Japan (January 2005), the idea of the three core university policies—Diploma, Curriculum, and Admission—has been disseminated by the government as the key approach to curriculum design in universities. Since April 2017, all universities are statutorily obliged to formulate and publish these three policies.

- Diploma Policy

A basic policy that prescribes, in accordance with the educational principles of the applicable university/faculty/department, what capabilities students are required to acquire in order to be approved for graduation and awarded an academic degree. States the desired learning outcomes for students. - Curriculum Policy

A basic policy that prescribes what kind of educational program will be offered, what educational content and methods will be used in its implementation, and how learning outcomes will be assessed, in order to achieve the goals of the Diploma Policy. - Admission Policy

A basic policy that prescribes what kinds of applicants will be admitted to the program, taking into account the educational principles of the applicable university/faculty/department and the content of the Diploma Policy and Curriculum Policy. States the learning outcomes that applicants for admission are expected to demonstrate (the achievements expected of applicants in the “three components of academic ability”*).

*(1) Knowledge/skills, (2) capacities for thinking, judgment, expression, etc., (3) preparedness to learn in a self-directed manner in collaboration with diverse peers

(From the guidelines of the University Subcommittee, Central Council for Education, March 2016)

- The three policies address the exit point (graduation) and the entry point (admission) of university education and the curriculum that occupies the space between these points, and each university is required to pursue educational quality assurance as well as systematization and visual presentation of its curricula. They are underpinned by the idea of “outcome-based education.”

- The policies of Kyoto University as a whole and each of its faculties and graduate schools are published on the university website.

2.2 Intended learning outcomes

- The shift from teacher-centered education to student-centered education that has taken place since the 1990s has drawn greater attention on the question of what students have actually learned rather than what teachers have taught.

- In the course of this shift, it has come to be expected that educational objectives are expressed in terms of “learning outcomes.” Learning outcomes “state the content that learners are expected to know, understand, act, and demonstrate at the end of a specified learning period such as a program and a course.” (translated from the glossary to the Central Council for Education report on undergraduate degree programs, 2008). What is notable here is that the term “learning outcomes” has come to refer not simply to the products of learning, but also to the objectives thereof.

2.3 Competence/competency

- Since the early 2000s or thereabouts, the term “competence” or “competency” has come into widespread use throughout the world as a way of expressing learning outcomes. Competence is an organic combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes and other components that students are expected to acquire as an outcome of their overall learning in a degree program.

- In its report on undergraduate degree programs (Towards Building Undergraduate Education, December 2008), the Central Council for Education proposed the concept of “graduate capabilities” (gakushiryoku) to indicate “the intended learning outcomes common across all undergraduate graduate education in Japan.” The Council tentatively proposed that gakushiryoku would comprise “knowledge/understanding,” “generic skills,” “attitudes and dispositions,” and “integrative learning experience and creative thinking.”

- A feature of this concept is the inclusion of generic skills as “skills necessary for both intellectual activity and vocational and social life.” Communication skills, quantitative skills, information literacy, logical thinking skills and problem-solving abilities are provided as examples of generic skills.

- Meanwhile, in light of the fact that many elements of competence, especially “knowledge/understanding,” differ across academic subjects, efforts are being made in collaboration with the Science Council of Japan to imbue the concept with more specific content.

2.4 Subject Benchmark Statement

- On the request of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), the Science Council of Japan conducted deliberations and submitted a response paper on subject-specific quality assurance in university education in July 2010. This paper proposed including the following types of content as benchmarks in the formulation of degree programs in specific academic subjects:

① Definition and distinctive features of the subject

② Basic elements to be mastered by students in the subject

(a)Basic knowledge and understandings

(b)Basic abilities: Abilities specific to the subject and generic skills

③ Basic approach to learning methods and assessment methods of learning outcomes

④ Relationship between the major specialization and liberal education in regard to the cultivation of citizenship

- Benchmarks are currently being formulated in each subject in line with this framework. As of April 2017, benchmark statements had been published for 25 subjects: management, linguistics and literature, law, domestic science, mechanical engineering, mathematical science, biology, civil engineering and architecture, economics, area studies, history, materials engineering, political science, geography, cultural anthropology, sociology, psychology, earth and planetary sciences, social welfare, electrical and electronic engineering, informatics, philosophy, statistics, agriculture, and physics and astronomy (Science Council of Japan website). These Benchmark Statements are a solid reference point for curriculum design in each subject.

2.5 Process of program design

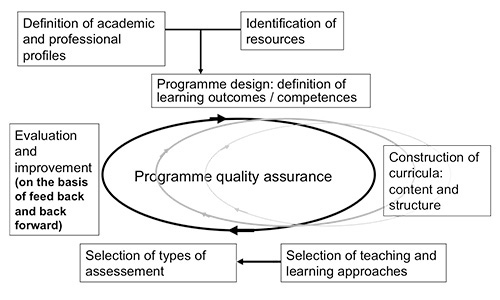

- A process of the type shown in Figure 1 is essential in order to design, implement and continuously enhance the quality of a program (especially degree program). “Academic profile” refers to the distinctive features of the subject as stated in the Subject Benchmark Statement.

For information on “Selection of teaching and learning approaches” see “Class Design”; for “Selection of types of assessment” and “Evaluation and improvement” see “3.6 Curriculum evaluation and improvement.”

Issues Related to Curriculum Design

There are other aspects that require consideration in the context of curriculum design

3.1 Scope and sequence

- Scope concerns the breadth of courses (or learning activities), while sequence concerns the order in which they are arranged.

- One of the issues debated in relation to sequence is the relationship between liberal education (general education) and the major. Restrictions on the categorization of courses―general education, foreign language, health and physical education, and the major―were abolished in the 1991 “deregulation,” making it possible for universities to offer foundational major courses from an early stage. There is also a reverse school of thought that affirms the benefits of having students undertake liberal education after they have completed a certain level of study in their major fields.

- Today, most Bachelor degree programs expose their students to actual work and scholarly pursuits at an early stage, providing them with an outlook on their future and motivation to pursue learning in their major. A typical example is the early exposure approach taken in undergraduate faculties of medicine. Early exposure involves students undertaking clinical experiential learning at actual sites of medical practice from shortly after they enroll. Approaches like this are underpinned by the idea that rather than following a unidirectional pathway from foundations to applications and from theory to practice, students should deepen their learning as they move back and forth between foundations/theories and applications/practice.

3.2 Semester/term/quarter system and credit hour

- Designing a curriculum is also a process of determining how to divide up the time from enrollment to graduation.

- For example, there is the question of how many teaching cycles the academic year should be divided into. In Japan, in addition to the traditional semester (two-cycle) system, in recent years some universities seeking to align with global trends have begun to adopt quarter (four-cycle) and term (three-cycle) systems.

- There is also the question of how many minutes to make each class period, and how many classes to hold each week in each course. It used to be standard in Japan to hold one 90-minute class period each week, but in line with the changes in the semester/term/quarter system, there are now other patterns such as 105-minute classes (e.g., University of Tokyo) and two classes per week (e.g., Hiroshima University).

3.3 Required and elective courses

- University educational programs are made up of required, elective, and optional courses. Even if an educational program is designed to achieve certain educational goals, if there is wide scope for choice, there will be less control over the curriculum that students experience. However, if all courses are made compulsory, students cannot design their own curriculum, and it becomes more difficult to cultivate independent, self-directed learners.

- Kyoto University’s faculties are diverse in this regard, ranging from those where almost all courses are required (such as the Faculty of Medicine) to those where almost all are elective (such as the Faculty of Science).

- One approach that can be adopted to deal with this dilemma is the “course system,” which allows students to select from among a number of different “courses” composed of groupings of classes.

3.4 Levels of degree

- One question that emerges especially in the era of universal access to higher education is that of how to organize a student body that is highly diverse in terms of academic abilities, learning motivation, and other attributes, and prepare programs suited to each student’s needs. It is already common practice in areas such as foreign language and information technology courses to allocate students to classes based on their performance in tests conducted before the start of the course.

- Moreover, in recent years, Japanese universities (e.g., Kyushu University, Ritsumeikan University, Ehime University, and Soka University) have started to establish special programs for high-achieving students, in line with precedents such as the honors programs offered in the United States and honors degrees in the United Kingdom. Honors programs are special academic programs targeting selected students and comprising elements such as small-group seminars, individual supervision, international activities, and community service activities. In this way, universities are seeking to ensure the “co-existence of diversity and excellence.”

3.5 Who designs curriculum

- It goes without saying that the primary actor in curriculum design is the university, faculty, or other educational organization and its faculty members. In the actual operation of curriculum, collaboration with administrative staff (faculty-staff collaboration) is also crucial.

- However, faculty and administrative staff members are not the only actors in curriculum design. The educational goals of a curriculum are realized through the action of students themselves in selecting courses from among those offered by their university/faculty, and actually undertaking and completing those courses.

- It is through the medium of students that a university curriculum becomes complete. Strictly speaking, university curriculum does not exist within pre-ordained educational programs, but rather is manifested through the paths taken by each individual student. A resume or personal history is sometimes referred to as a “curriculum vitae”; in the same way, the university curriculum denotes a history of learning.

3.6 Curriculum evaluation and improvement

- If we accept that a university curriculum is only manifested as curriculum through the medium of its students, then it is essential to ascertain what kind of curriculum students have actually experienced and what kind of learning outcomes have been achieved, and then to think about ways of improving the curriculum. The issue here is curriculum evaluation and improvement.

- In recent years, in addition to evaluation of individual student performance in each course and evaluation of teaching by students, there are many different types of assessments that can be utilized to evaluate curriculum (see Assessment of Teaching and Learning).

References

Central Council for Education. (2008). Gakushi katei kyôiku no kôchiku ni mukete (Tôshin) [Towards building undergraduate education (Report)].

Central Council for Education. (2012). Aratana mirai o kizuku tame no daigaku kyôiku no sitsuteki tenkan ni mukete: Shôgai manabi tsuzuke shutaitekini kangaeru chikara o ikusei suru daigaku e (Tôshin) [Towards a qualitative transformation of university education for building a new future: Universities fostering lifelong learning and the ability to think independently and proactively (Report)].

González, J., & Wagenaar, R. (Eds.). (2008). Tuning Educational Structures in Europe, Universities’ contribution to the Bologna Process: An introduction (2nd ed.). Bilbao: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Deusto.

Matsushita, K. (Ed.). (2010). “Atarashii nōryoku” wa kyōiku o kaeru ka: Gakuryoku, riterashii, kompitenshii [Will the “new capabilities” change education? Academic ability, literacy, and competency]. Kyoto: Minerva Shobo.

Matsushita, K. (2012). “Daigaku karikyuramu” [University curriculum]. In Kyoto University Center for the Promotion of Excellence in Higher Education (Ed.), Seisei suru daigaku kyōikugaku [Generative studies of university education] (pp. 25-57). Kyoto: Nakanishiya Shuppan.