TopicsTeacher Interview

From "Kyoto Method" to "Flipped Classroom": A New edXational Strategy Spanning Overseas Universities

Professor Motonari Uesugi, Institute for Chemical Research and Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (WPI-iCeMS), Kyoto University

Professor Uesugi teaches "001x The Chemistry of Life," a MOOC designed to facilitate idea generation skills at the interface between chemistry and biology. Since April 2014, the MOOC has been offered annually for the past five years*. In this exclusive interview, Professor Uesugi shares his behind-the-scenes stories, including how Kyoto University's first MOOC started and why he has implemented the interactive teaching method as an emerging teaching model.

*The 2018 version is technically its fifth round (as of May 2018 at the time of publication of this article), yet the article refers to the MOOC as the "fourth year" since the interview with Professor Uesugi was recorded in January 2017 when the course was still in its fourth round.

If It's Going to Be Done, Do It Thoroughly, and Name It the "Kyoto Method"

Professor Uesugi, you've been offering the MOOC for four years now. Can you tell us what led you to teach this course in the first place?

One day, I received a phone call from the former Kyoto University President Matsumoto. He goes:

"You know how online courses are spreading these days? We've just received an offer from edX. When I ran through a list of professors in my head and thought about who could take this for real, your name first popped into my head. So, can you do it?"

Did you agree then and there?

Honestly, I thought it was going to be a really hard work, but the next moment I found myself saying "Why not? I'd be delighted!" (Laughing)

So I promised myself: since I'm the one who's doing this, I should rather do it thoroughly and extensively, and achieve something as revolutionary as naming my online education style the "Kyoto Method." From then on I proposed a number of ideas that I thought might be appealing to the then President. The bottom line is, if you don't ever enjoy doing what seems challenging, it is just a burden; if you dare to enjoy yourself along the way, it won't give you much of a hassle. (Laughing)

The "Kyoto Method"? Tell us more about how you invented the method.

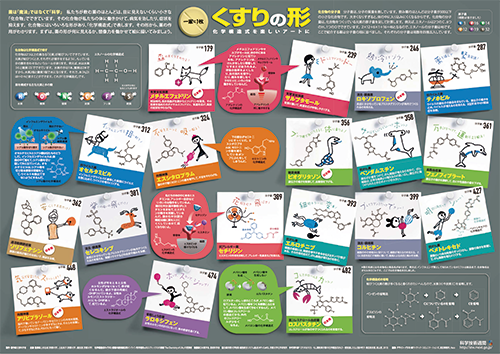

"One sheet in every household: Shapes of Drugs" created from Professor Uesugi's Drug Constellation assignment (Click to enlarge)

The first attempt was the "Drug Constellation," the very first assignment from Week 1.

In my regular face-to-face classes, I ask students to illustrate their ideas in handwritten chemical structures with drawings. This is very handy as I could let the students stay away from the culture of copy-and-paste, and the speed of screening and evaluation increases on my side. I adopted the same method to my MOOC, incorporating special software into the edX site as a solution to online chemical structure drawing and freehand drawing.

For the Drug Constellation assignment, I asked students to pick one of the 100 best-selling small-molecule drugs, re-draw its chemical structure, and draw an illustration that well symbolizes the structure. It sounds tedious if you simply memorize star positions in the sky. The same task could be more engaging if you see the starts forming constellations. In the same theory, the Drug Constellation assignment transforms chemical structures into a more interesting memory game.

"Virtual to Real" Experience with the First MOOC

Drug Constellation? But grading students' assignments must have been time-consuming, given the number of students taking the course.

The approach to grading is another key feature of the Kyoto Method. For the Drug Constellation and other in-course assignments, we implemented a method so-called peer evaluation to streamline our evaluation efforts. As a starter, students were assigned to evaluate each other's assignments, then the course team curated only the ones ranked in the top tier, which the team graded manually.

Amid the first round of the course series, six top-performing students were invited to visit Kyoto. Out of the 20,000 candidates taking the course, just over 80 were shortlisted after peer evaluation and follow-up grading. These students were then given further advanced assignments, including YouTube-based presentations, and in the end, the final six were selected based on their performances in those assignments.

This is what you mean by saying "from virtual to real," right?

The six top-performing students during their invitational visit to Japan (image supplied by iCeMS)

Exactly. I once asked the then President Matsumoto if he had any ideas about how we could make Japan's first edX course an iconic success. The President said: "Since you have a pool of 20,000-plus registered students, why don't you select a few of the top-performing ones and invite them to Kyoto?"

I replied: "That's a great idea! You must be aware though that implementing the plan will cost us some. Over to you, President!" The President did fund us for the invitation program and eventually invited all six of the top-performing students.

The students came to Kyoto for real, and attended one of my real face-to-face classes. What impressed me was that each one of them was literally an outstanding student: to be honest, I hadn't expected our online selection process would be this accurate. Later on, two of the students won the Japanese Government Scholarship, and joined my research group as graduate students.

"Killing Two Birds, even Three Birds with One Stone," Including Education for On-Campus Students

What was the hardest part initially about offering an online course series?

First there was the filming. I had been teaching face-to-face classes for many years and was well-accustomed to the style, but I had never before had a chance to teach to a camera.

From Professor Uesugi's MOOC. Most of the filming was done within the iCeMS building.

One of the first approaches I tried was to teach in front of a real "audience" in the filming studio. (Laughing) I invited four or five international students studying at Kyoto University and filmed some clips as if I was teaching at them. Well, it didn't work out; perhaps some of my nervousness got transferred to them, so the atmosphere in the studio ended up quite tense, with the students sitting quietly with no laughter.

After this experiment, we decided it would be best to film with no audience. We finally settled in the venue I used for my regular classes, on the second floor of the iCeMS building, filmed with just the production crew present. In the end, you just have to get used to it.

Surely there were many challenges to overcome when preparing assignments, especially peer evaluation.

Preparing the assignments wasn't actually so tiring, because I was helped out by Dr. Amelie Perron, who was a Research Associate in iCeMS back then and was later promoted to a Senior Lecturer. Besides, peer evaluation, as the name suggests, is simply a matter of students evaluating one another automatically, and didn't require any special attention from our side once its format had been designed. A comparison showed that those assignments scoring highly in peer evaluation were of better quality than those that didn't, so it seems that the system functioned effectively.

One good thing about this system was that we had the ultimate goal of selecting top six students, when we reached the phase of grading the assignments of the 500 highest-ranked students in peer evaluation. If we hadn't set the goal, it would have been more difficult to get us motivated. By also taking the benefit of teaching a face-to-face course at Kyoto University around the same period, I asked my real course students to join me on the journey of the grading process in class. By doing so, as well as getting done with grading hundreds of online assignments, I was able to use the grading process as an educational exercise for Kyoto University students, and jointly select top students to invite to Kyoto. All in all, our continued efforts turned out to be "killing two birds, or even three, with one stone."

Flipped Classroom: The Greatest Advantage of MOOCs

Have you changed personally in any way over the four years that you've been running this MOOC?

Yes, in many positive ways. First of all, I've become accustomed to filming classes. Secondly, I think I've come to appreciate what online teaching has to offer. If I think of my conventional teaching format as "live," then teaching in the MOOC is like a television show, where I have to attend to the phrases and expressions that I use, and pay attention to many other aspects besides.

Professor Uesugi says that teaching a MOOC is tough, but that he feels the hard work pays off in the end.

At first I was bewildered by these gaps, but once I got used to them, I started to feel the benefits of delivering classes in English to a global audience, and having so many students participate.

Filming and other parts of online teaching are hard work, but I feel that it all pays off in the end.

The third change relates to the Flipped Classroom approach. If it wasn't for the MOOC, I would never have started taking this approach. The biggest change over the past four years is that I've learned how to run a Flipped Classroom.

Your name is strongly associated with Flipped Classrooms, isn't it?

Yes. Earlier I explained that I started the MOOC after being approached by the then President Matsumoto. At the first press conference we held about the MOOC, one journalist asked how launching a MOOC would actually benefit Kyoto University.

The press conference held on the launch of Kyoto University's first MOOC (image supplied by iCeMS)

Our reply was this: "Issues such as what the benefits are for Kyoto University are minor concerns-what we are doing here is part of a global social experiment."

Generally, technology creates disparities. The question is how to address those disparities with the power of technology. MOOCs provide an answer. "Anybody can participate in a class taught at a top-ranking university, as long as they can understand English and are connected to the internet. How could this change the world? This is a social experiment on a grand scale."

I didn't think of what would happen at that point, but if I were asked the same question again today with the benefit of four years' experience, my answer would be: "Flipped Classrooms."

Are Flipped Classrooms such a big deal?

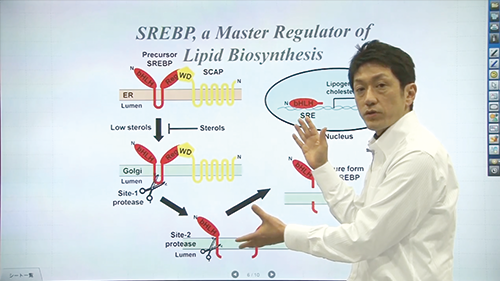

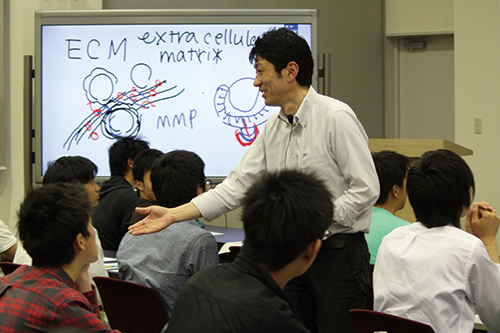

Professor Uesugi's Flipped Classroom in action. In the face-to-face class, students are encouraged to speak out proactively.

Yes, they certainly are. By introducing the Flipped Classroom approach, I've been able to make my real classes here at Kyoto University more interactive. Learning has become more efficient because students can watch the lecture online at home, and concentrate on practical exercises and discussions in class.

I personally think that at Kyoto University, the Flipped Classroom approach should be followed by all courses where online lectures have already been produced and available. In fact, student survey also shows that many students are interested in taking more Flipped Classroom courses.

A number of other professors offering MOOCs have also employed the Flipped Classroom approach, haven't they?

That's great. That's a major benefit for Kyoto University, I think.

Running a MOOC was a grand social experiment, as I said when we first started, but by trying out the Flipped Classroom format, now I can see practical benefits that I wasn't aware of at the outset.

Use of Global MOOCs Fostering Greater "Consciousness" Among Japanese Students

Is there any difference in this regard between offering MOOCs on "global" platforms such as edX and Coursera, and offering Japanese-language MOOCs?

If we're talking about Flipped Classrooms per se, I think it's fine to offer them in Japanese. The downside is that a lecture video that you make in Japanese will only reach Japanese speakers, which probably wouldn't achieve the "killing two birds, with one stone" effect by itself.

A professor aiming simply to adopt the Flipped Classroom approach could produce and publish their own lectures in Japanese, and use them in their own classes. That would be "one bird, one stone."

If other professors say they want to use the lectures, let them do so. Yet, this is still not quite "killing two birds with one stone." Apparently, only one to two percent of the world's population can understand Japanese. I believe that the "two birds" stage can only be reached if the Flipped Classroom is accessed by large numbers of people and contributes an answer to the social experiment I mentioned earlier.

I found that another benefit of offering my course in English was that my real course students became more confident. At first my students were uncertain whether or not they'd be able to keep up with lectures in English, but all of them could handle it when they gave it a try.

In the student survey there were comments such as, "I realized how important English is." It seems that by actually seeing people from around the world taking the same class as them in English, students not only gained a feeling for the wider world, but realized that they needed to use English themselves, and that this was only normal.

More Flexibility in the Face-to-Face Classes, Generated as a Result of the Flipped Classroom

One thing I noticed when observing your classes was that apart from naturally allocating time to assigned tasks, you also leave plenty of room for commenting on them and supplementary explanation of the content of the lecture video.

Is this something you take particular care with?

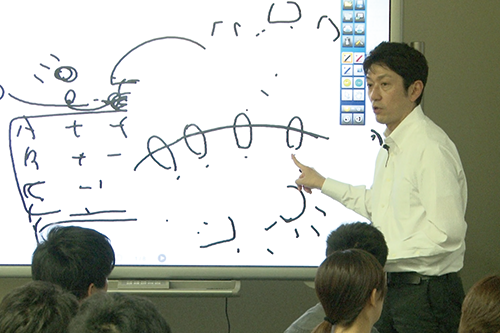

Professor Uesugi adding some extra comments in a Flipped Classroom. Behind him is the electronic blackboard that was used in filming for the MOOC.

I think a lot about that aspect myself. The students have all watched the video before class, so in a certain sense we can proceed flexibly.

Before I started using the Flipped Classroom approach, I used to just provide explanations. Flipped Classrooms have enabled me to devote time to assigned tasks and commentary.

Even if you begin with some small talk seemingly unrelated to the topic, eventually you're always able to connect that with a discussion on the generation of ideas.

That's so-called "tailoring (awase)." The initial topic may seem completely unrelated, but eventually it connects in some way. It's a basic technique of Japanese Rakugo comic storytelling, known as shikomi-ochi, or setting up the punchline. It's really effective.

The Flipped Classroom has made it easier to manage my time, so I have now more scope to tailor the discussion in this way.

Demonstrating the Flipped Classroom Approach for Instructors Overseas: Preparatory Learning via MOOCs, Face-to-Face Classes with Local Instructors

So the positive mood and tempo of your classes comes partly from the Rakugo tradition! I hear that you are also trialing the Flipped Classroom approach overseas.

Yes, that's part of a JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) international program.

The program is called ACBI (Asian Chemical Biology Initiative), and involves sowing the seeds of the discipline I work in, chemical biology, in emerging countries in Asia.

ACBI-Sponsored Class series is run as part of this program. These involve going out to emerging Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia, and providing classes. I get local students to view the MOOC in advance, then I come over and run a Flipped Classroom. The other day I did one at Fudan University in China. It was attended not only by students, but by faculty members as well.

Faculty members attended too?

Yes. A number of young faculty members of Fudan University were there.

What I want to do in ACBI-Sponsored classes is to provide local instructors with a model for a different kind of teaching. Ideally, I'd like them to take on the Flipped Classroom approach, and I tell them that they're welcome to use my MOOC if required.

So your MOOC is used for preparatory learning, and then local instructors run the face-to-face classes?

Professor Uesugi explains his desire to provide a model for Flipped Classrooms.

Exactly. That's the model I want to provide. It's best if I can show them how to do it in practice and inspire them to try it out themselves, using my MOOC but running the actual classes themselves, in the local language. I hope that overseas universities follow the innovative and interactive teaching approaches that I try here at Kyoto University.

Ideas for Sharing Teaching Resources, Inspired by MOOCs

But isn't it difficult to implement in practice?

That's true. Flipped Classrooms are not easy to run, but students enjoy them, and nobody sleeps in class! Efficiency in teaching methods is sure to improve. These days it has become much easier to access all sorts of knowledge online, but if you prioritize improving students' skill sets in generating knowledge, Flipped Classrooms are a great option.

In terms of reducing the burden on instructors, there is one other thing I'm working on with colleagues overseas: sharing of teaching resources. Just the other day, 45 professors specializing in chemical biology from Japan, South Korea, China and Singapore gathered in Ho Chi Minh City to discuss this topic.

Sharing of teaching resources?

That's right. Each of us is teaching chemical biology at his or her own university. If we're all teaching the same thing, why don't we bring together and share our slides, videos and other resources in our areas of expertise? This approach can contribute to streamlining class preparation efforts.

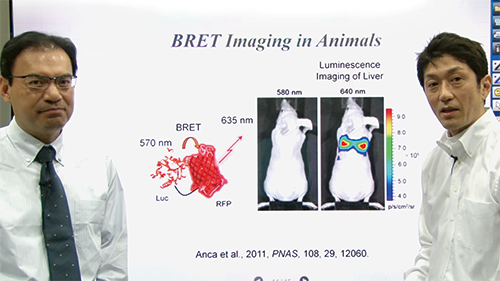

Another feature of Professor Uesugi's MOOC is the occasional guest appearance by other researchers in the same field. The person on the left is Professor Takeaki Ozawa from the University of Tokyo.

Professors at top universities really want to spend their time on research. We want to enjoy our teaching as much as possible, but don't want to devote too much effort to it. If we have such time and energy, we'd prefer to be doing more of our own research.

At the same time, as teaching is our responsibility and what should be done properly, we want to make it both enjoyable and productive. Saving enormous time on class preparation can be a major incentive.

Did you come up with those ideas in the course of working on the MOOC?

Correct. Teaching more efficiently, offering classes globally, and being an Asian professor rather than a Japanese professor were all things that I'd thought about before the MOOC, but I didn't have any concrete ideas. It was through running the MOOC that I hit upon ideas such as Flipped Classroom and sharing of teaching resources.

In that sense, I feel rewarded for working on the MOOC as it has turned out to be a positive "killing two birds, or even three, with one stone" experience. I will continue to revise the contents of the MOOC into the future, and hope that it has an impact on many people throughout the world.

Thank you for taking time out from your busy schedule.

Questions asked by: Hiroyuki Sakai, Mana Taguchi, and Yoshimi Kozai

Article composition: Takeo Suzuki

Interview date: January 26, 2017

Published online: May 28, 2018

Click here to get more information on KyotoUx.