TopicsTeacher Interview

Use of Live Comment Posting Tool in Lectures Brings Lecturer and Students in Sync

Senior Lecturer Hiroaki Mizuhara, Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University

In April 2016, a certain lecture course at Kyoto University became a hot topic on Twitter. What has caught people's interest in these liberal arts and sciences lectures is that during classes students can post comments that then appear on the slides displayed on the lecture hall screen, in a similar style to that of the Japanese video-sharing website Niconico Douga, where users' comments are overlaid onto videos in real time.

We spoke to Dr. Hiroaki Mizuhara, the faculty member who proposed this teaching style, to find out what a "Niconico Douga-style lecture" contains, and the thinking behind the decision to adopt such a format. Our chat with Dr. Mizuhara revealed a faculty member who is drawing on the results of his specialist research to devise improvements in teaching methods.

- PROFILE

- Ph.D. in Engineering and Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Division, Department of Intelligence Science and Technology, Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University since 2007

- Previously, Researcher at RIKEN Brain Science Institute and Senior Lecturer at Okayama University

- Received a number of awards, including a distinguished presentation award from the Japanese Society for Cognitive Psychology and an excellent research award from the Japanese Neural Network Society

- His main papers including "Human cortical circuits for central executive function emerge by theta phase synchronization" (Mizuhara, H. & Yamaguchi, Y., NeuroImage 36, pp. 232-244, 2007) and "Top-down and bottom-up attention cause the ventriloquism effect with distinct electroencephalography modulations" (Kumagai, T. & Mizuhara, H., Neuroreport 27, pp. 647-651, 2016)

- His hobbies being fishing and supporting the baseball team Hiroshima Carp

- Adopts a minimalist approach to try to keep his laboratory as free as possible from unnecessary items

Papapa Comment (Live Comment Posting Tool) Incorporated in Large Lectures Following Trial and Error

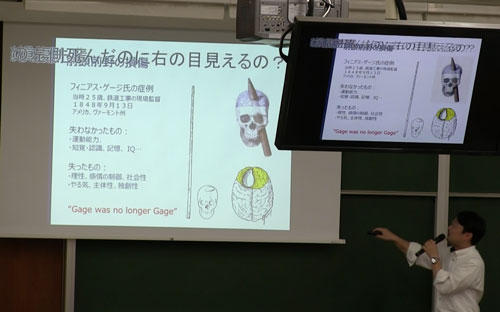

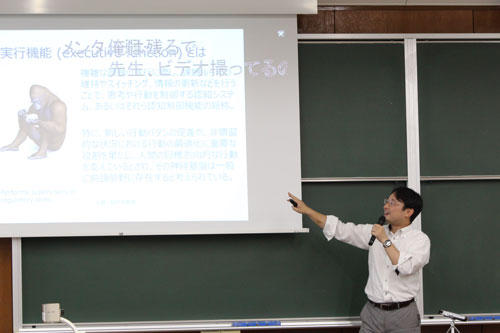

The photos above show a Niconico Douga-style lecture. Comments from students appear on the lecture slides, in the style of the video-sharing website Niconico Douga. The lecturer sees the screen and responds to questions that students post as comments. (Photos taken on July 21, 2016.)

*As Dr. Mizuhara's lectures had already finished when we conducted this interview, here we used photographs of a lecture by Associate Professor Satoshi Tsujimoto (Graduate School of Informatics), who teaches the course with Dr. Mizuhara. The classes are described as "relay lectures," as the lecturers take it in turns to teach classes based on their expertise.)

Let's start by looking at the format of classes. Can we describe them as "Niconico Douga-style" lectures?

Yes, although technically we use a publicly-available tool called Papapa Comment, it is something different to the pioneer of the format, Niconico Douga. Papapa Comment is a beta-version tool that was made available by Recruit Holdings, Co., Ltd. ("Recruit") around seven to eight years ago. It can be used by simply installing it on the lecturer's computer.

Students don't need to install anything. By accessing the Papapa Comment website and typing in the relevant "room name" set in advance by the lecturer, students can send comments which are then overlaid on the slides displayed in the lecture, via the lecturer's computer. All the students need to do is be online.

When did you start using this lecture format?

Since I discovered Papapa Comment about six or seven years ago.

Initially, I started using it in lectures for graduate students with around 40 attendees. I tried it out for about two years, but it wasn't very interesting, because the students weren't posting many comments. Later, I had opportunities to give talks to around 100 participatnts at conferences and other such events. When I tried using it on those occasions, I got a response.

I was making various attempts to try it out, but it was when I used it in a lecture I gave outside of the university on the topic "An Introduction to Statistics" that I became convinced it could work. Statistics can be a rather solid subject, and it also involves things like expanding formulae. My approach is to write explanations out on the board, and when students didn't understand the expansion of a formula, I quickly got a stream of comments from students, saying things like: "It's hard to see what you've written," or "I don't understand that expansion."

That gave me the feeling that the format could be effective, and I decided to try using it again here at Kyoto University. The lecture that you've seen, "Basic Neuroscience," is a course that started last year. I decided to give the format a try when I heard in advance that it was going to be a liberal arts and sciences course for several hundred students. The response was positive, so we have continued to use the format this year.

And it has even been featured in stories online.

Yes, but that wasn't last year. The lecture format didn't attract special interest online until this year. Apparently, some people outside the university-particularly people in the field of psychology-have picked up on the excitement surrounding it online and started using the same tool.

Quick-Witted Dialogue and Deeper Understanding Generated by a Tool for Stimulating Students' Interest

What do you think are the key merits of using this tool?

As you might guess, I think a significant benefit is the fact that students show interest in the class and the slides. Especially when it's a large lecture with as many as several hundred students, if you don't make efforts to keep students focused, they will quickly get bored and doze off or not look to the front. So, my first aim was to ensure that students look to the front, and keep looking to the front. With this tool, when a stream of comments starts filling the screen, it might include an interesting comment or two, so students look to the front to avoid missing something interesting. That was the first obvious benefit.

In the process of trying out the format, I realized that it also helps me to see what areas students don't understand, and what kinds of things are difficult for them to understand. I made sure to go through such areas again, and it seems that this has helped to develop students' understanding.

Yes, after all, it's hard for students to speak up and say they don't understand something in a lecture with as many as several hundred students, isn't it?

Well, yes, it's incredibly difficult for students to do that.

Are there some questions from the students that you find particularly impressive?

Yes. When a student who already has some knowledge of the field asks a question that delves a bit deeper, or a student has a good question, regardless of their prior knowledge of the topic, I add in explanations on topics I hadn't originally planned to talk about. I think that such opportunities to expand the topic are also considerably beneficial.

But on the other hand, haven't there also been occasions when the comments have gotten out of control?

That certainly happens! Particularly, at the start, because students try to have fun with it.

But in the first lecture of the course, I make sure to tell students that I will stop using the system if the comments get too bad. I explain that that won't be in anyone's benefit, so they should try to exercise moderation. If I do that, the comments don't get too out of hand.

At the same time, you probably won't be surprised to hear that we still get some comments that are honestly quite trivial. I make a point of not responding to those ones, and eventually the students who write them give up. When they're ignored, they realize that there's no point in making such comments, so instead they start to try their best to think of comments that will prompt a response.

So instead of questions that are too silly or trivial, do they try to come up with slightly tricky ones, even just to fool around?

Yes, sometimes they even go for topics that don't have anything to do with the lecture. When something like that happens-such as a student going for a silly topic-sometimes I'll make a good comeback or turn it into an opportunity to link it to some area of neuroscience. While they might have started with a silly question, such chances to take the lecture in a different direction are actually quite interesting.

How Our Brains Synchronize: Human Communication from the Perspective of Cognitive Neuroscience

We've heard that you specialize in cognitive communication, and your research explores using MRI and other such measuring methods to clarify the connections between verbal and non-verbal communication and the workings of the brain.

What kinds of observations can you make about this lecture format from your specialist point of view?

I just recently had the opportunity to write a column on that topic for a newspaper published by university students (Kyoto Daigaku Shimbun).

My specialist field is related to communication, and in recent years I have been focusing my research on synchronization.

Two metronomes each with different amplitudes synchronize with each other.

The same can be said of the process of human communication, explains Dr. Mizuhara.

To give you an idea of what this means, I'd first like to show you this video (editor's note: the video to the left). There are two metronomes, each made to go backwards and forwards at different timings from each other. As long as they are left moving as they are, they will continue to swing at different timings. However, if the metronomes are placed on a board, with two cans underneath, this allows their momentum to spread to each other, and the needles quickly begin to move in sync.

The way that fireflies blink in unison is a well-known example of such a phenomenon. In fact, such synchronization also occurs within our brains, which leads to the idea that the same can be said of human communication. In other words, in the brain it is normal for a certain part to be responsible for a certain function, and for the different parts to each have different workings. However, when we do something, it is not possible to bring something about if just one part processes the information alone, so distinct parts each responsible for distinct functions synchronize according to the situation, allowing the respective information that they hold to fuse, and generate mental ability suited to the situation.

This prompted me to investigate whether the same can be said of communication between humans. To do this, I have recently been investigating oral communication. It is a known fact that speech itself has a rhythm. On this basis, I am starting new research to explore whether such rhythm prompts synchronization between one person's brain and another when they are speaking to each other, and whether synchronization between one person's brain and another causes two sets of knowledge to fuse and generate new knowledge.

In that sense, in lectures it is also the case that if information is only flowing one way, it is difficult for synchronization to occur, but if power is transmitted in both directions, this facilitates synchronization and allows for the communication of information. However, in a typical lecture, where one side is the lecturer and the other side is the students, the information from the students doesn't really reach the lecturer. And even if there's just information from the lecturer, in terms of the physical principles, synchronization may at least be possible, but it will be highly inefficient. If the lecturer's metronome is influenced by the oscillation of the students', this eases synchronization, and as they adopt the same timing, it becomes easier for them to communicate with each other. This is the kind of concept behind the lecture format I am currently pursuing.

So, in terms of the video you just showed us, Papapa Comment is like the board on top of the two cans?

Yes, exactly. The point is that Papapa Comment serves as the tool to prompt synchronization. Such phenomena have also been clarified in theoretical terms. Professor Yoshiki Kuramoto, professor emeritus of the Kyoto University Faculty of Science, has been researching this area for many years, and some researchers are currently pursuing similar research on the brain to investigate whether the same thing can be said of what occurs within the brain.

Guaranteeing the Quality of Learning in One-Time Opportunity Lectures

You said that it was last academic year when you first started to use this system in liberal arts and sciences lectures. Do you think it has been effective for students' learning?

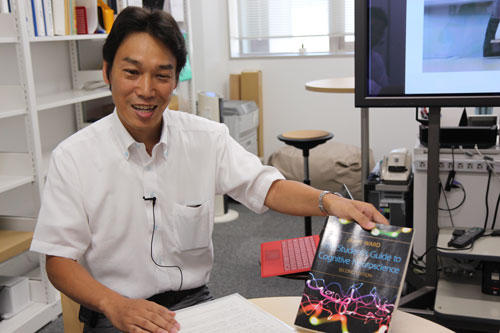

Dr. Mizuhara holding the textbook used in the lectures. He selects the materials for the course from this textbook and makes them into slides. He also explained that he is always careful when selecting the content, because the students taking the course are from a variety of faculties.

As far as I can tell from the feedback we received from students in last year's lecture evaluation questionnaires, I think that it has had an effect. It seems that a fair number of students have sensed that we are putting effort into devising the formats for lectures. For instance, although it is quite normal for the number of attendees to decrease toward the end of a course, in this lecture (editor's note: Associate Professor Tsujimoto's last lecture of the first semester-the lecture covered for this article), of the over 400 students registered to take the course, over 300 attended. I think that's a relatively large percentage for a liberal arts and sciences course at this point in the academic year.

At the same time, naturally, not all of the feedback is positive. Some students comment that they don't like the format. We've received feedback saying that the text coming up on the screen is distracting and makes it hard to concentrate. In fact, apparently some chose not to take the course because they preferred to avoid such a format.

But I have also taken this in mind as far as possible. My approach is to write up explanations on the board, and I largely use the blackboard and only put up certain diagrams on the screen where necessary. I also upload those slides to KULASIS (editor's note: Kyoto University's Liberal Arts Syllabus Information System [KULASIS] is an online system compiling university-wide academic affairs and information) a week before the lecture, I tell the students to download the slides from there and look through them before class. I include comments on the diagrams on the slides so that students can prepare for the lecture.

I make such adjustments to ensure that as many students as possible are able to take the course. But, of course, depending on the student, those efforts may simply be counterproductive.

It's true that large class sizes make it all the more difficult for lecturers. Are there any other such things you have done to try to improve the lectures?

I always give students the time to take photos of what has been written on the board with their phones. This is because I want them to be focused on listening, rather than taking notes, during the lecture.

I tell the students that when they start their careers, it will be more important to know and understand things, as opposed to just memorizing them. With that in mind, I also allow them to bring whatever materials they need to exams-that is, apart from phones or other such communication devices.

Is there a reason why you make a point of writing on the board?

Well, I have continued to write out explanations on the board because for some students there are things that are very difficult to understand unless they are written out in an analog-that is, non-digital-format. I don't think it's the case that everything needs to be digital.

That makes sense.

On a related note, I also emphasize the fact that a lecture is a "one-time-only chance." Students can only hear a class in real time once. This is the key point about lectures-a certain lecture can only be heard at one certain timing. With that in mind, when questions come up in class-as long as they are serious ones-I try my best to actively pick up on them, and probe the issues raised as far as I can.

Not Necessarily "Burning with a Passion for Teaching," but Keen to Make the Process Fun: Creating the "Positive Associations" That Encourage Students to Learn

What would you say is the source of your motivation to put such enthusiasm into improving classes?

There are two main things. Firstly, there is my wish for students to see the fun in neuroscience. To help them to do that, I'm also keen to ensure that they develop "positive associations," or in other words, positive feelings, that they connect with the discipline. If they link it with negative feelings, the very field of neuroscience will no longer be interesting for them.

Dr. Mizuhara describes himself as a lecturer who "may not be burning with a passion for teaching." When we fish for more, asking if it isn't a tough job all the same, he cheerfully replies: "Yes, I am always trying my very best to address students' needs and interests sincerely. If I'm honest, it's hard going."

The graduate school I belong to, the Graduate School of Informatics, doesn't have a faculty, so all students join us from graduate level. We are happy to see more and more students joining the field after hearing about it in lectures and developing an interest in the graduate school because it covers neuroscience. Such benefits are the first kind of thing that boosts our motivation.

The other is related to the fact that-like a number of people who teach at university-I may not be burning with a passion for teaching, but I think that if I'm going to do it, I should make sure I enjoy it. If the lecturer isn't enjoying the class, it will simply be wasted time for both sides, so I think it's important to do things that I find fun and interesting. When I communicate with the students and get them laughing because of a joke I have made, it's fun for me too. And vice versa, there are also times when a student's comment makes me laugh as well. I want to ensure the lectures include some fun elements.

How do you divide the work up with your course co-lecturer Associate Professor Tsujimoto?

You said that you personally were the first to use Papapa Comment. Did you have any trouble when deciding on the lecture format as a result?

Not really. We draw up the classes by choosing a textbook that will act as a basis. We aim to complete a textbook each half-year, by covering a chapter each class. Associate Professor Tsujimoto and I simply choose which chapters we are each going to cover.

It was this year that Mr. Tsujimoto started using Papapa Comment. And initially I just started using it, without mentioning it to him. When there was positive feedback from students about Papapa Comment in last year's lecture evaluation questionnaires, and it received a lot of attention online this year, it was a natural development for him to start using the same approach.

So, it wasn't like you based the lectures on Papapa Comment from the start?

That's right-Papapa Comment certainly wasn't the basis for everything. I just started using it for fun. And it's not like I actively introduced it to Mr. Tsujimoto.

Dr. Mizuhara's colleague Assoc. Prof. Tsujimoto using Papapa Comment in a lecture. There was a calm and friendly atmosphere throughout the lecture.

As far as we can tell from the lectures, Associate Professor Tsujimoto doesn't find it that bad at all!

(Laughing) Yes, I guess Mr. Tsujimoto is quite a fan too!

So, you don't really have disagreements or other problems about it?

No, we don't. Because our styles of teaching are completely different-for instance, Mr. Tsujimoto uses slides for each point he covers, while for me, it's important to write explanations out on the board.

Interactive Communication between Students and Lecturers: A Key Point when Considering the Benefits of Lectures in the Classroom

Has there been any response from your graduate school, the Graduate School of Informatics, or from other lecturers teaching liberal arts and sciences courses?

Now you mention it, there has been absolutely no response from within the university! On the other hand, as I mentioned at the beginning of the interview, I've heard it was being adopted by lecturers outside the university. I've asked how it is going, and apparently, they have also received positive feedback.

Are you interested in publishing the format as an established methodology?

Yes, I'm also hoping that the university's central administration will help with that.

As I partially explained at the start of the interview, the tool we use, Papapa Comment, is a beta version-it's been test run as a beta version for about seven to eight years now, so Recruit could easily stop operating it at any time. That is also clearly specified in the terms of use. I think that it would be a real shame, and a real problem, if it stops being available.

So, I think it would be great if the university could develop such a tool. If the system was managed using student ID numbers, that would probably put a stop to inappropriate comments. While I'm not sure if that's the best idea, I think it would allow more lecturers to feel comfortable about using it. And, after all, we can't expect Recruit's Papapa Comment system to provide such an identification function for us.

Although, the reason why I just said I'm not sure if it is the best idea is because it could make students feel hesitant to use the tool, which would do away with all the interesting comments. If students can't enjoy the lectures in an environment open to laughter, they won't develop those "positive associations"-that is, they won't connect the memories of what they have learned with positive feelings. That would make the approach quite meaningless in terms of what I originally sought to achieve with it. So, I think that we would need to try it out before we can say that controlling the system to that extent would be an effective step.

It's true that if all comments can all be checked alongside users' personal information, students might have their concerns about using it.

On the technical side, what potential is there for developing such a tool?

In technical terms, I've heard that the system uses Adobe AIR, but while I'm a member of the Graduate School of Informatics, my specialization is neuroscience, so unfortunately, I can't develop it myself. But for someone who knows how to do it, it's probably not that difficult.

So, given the resources available to the university, you'd really like their support for that.

Yes, that's right.

Finally, like your stance to teaching, I think there are many other lecturers at Kyoto University who believe that if they are going to teach, they want to make the classes more interesting and effective. Do you have any advice, tips, or messages for lecturers exploring the possibility of such new approaches?

Dr. Mizuhara, who was friendly and cheerful throughout the interview.

(To his right sits Program-Specific Associate Professor Motoko Okumoto, from the Center for the Promotion of Excellence in Higher Education, who conducted the interview)

It might seem a bit cheeky for someone like me to give advice, but I would like to say that I think interactive lectures-or in today's terms, "call and response" lectures-are incredibly important.

As I just mentioned, our research on the brain in relation to communication has shown us that it is difficult for information to be transmitted if it is just flowing one way. I think it's important to take a dynamic approach by which you judge what students are thinking as suits the particular situation.

To put it in the extreme, if classes don't have such elements of interaction, the lecturer might as well just put on a video instead of teaching themselves. In terms of the potential objectives of us lecturers making the effort to go and teach a lecture in person, I think that a key benefit is being able to see the students' reactions as we do so, and such interaction should be emphasized as an important point of teaching.

It was really informative to speak with you. Thank you very much for taking the time.

Thank you for the opportunity.

After we finished the interview, Dr. Mizuhara told us the following anecdote, which he said demonstrates a "side-benefit" of adopting the lecture style:

In the graduate course where I was trying out the Niconico Douga-style lectures, one of the students had hearing problems. He always sat at the very front of the lecture hall, so he could just about hear what the lecturer was saying, but he couldn't pick up what other students were asking, which always made him feel uneasy. One day, after the lecture was over, he came to thank me. He said that since I had started doing these Niconico Douga-style classes, he could understand the questions from the other students and get a sense for the response. He told me that was the first time he had been able to do that.

It was a moment that reminded me that the efforts of each member of teaching staff have the potential to change students' very experience of learning.

Questions asked by Motoko Okumoto and Takeo Suzuki

Article composition: Takeo Suzuki

Interview date: July 22, 2016

Published online: May 15, 2017 (Original article)

May 7, 2018 (English article)